Large ozone hole detected over Antarctica

Satellite measurements over Antarctica have detected a giant hole in the ozone layer.

The hole, which scientists call an “ozone depleted area” was 26 million square kilometers (10 million square miles) in size, roughly three times the size of Brazil.

The European Space Agency Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite made the recordings on September 16, 2023, as part of the EU’s environmental monitoring program.

Claus Zehner, the agency’s mission manager for Copernicus Sentinel-5P, told DW that this is one of the biggest ozone holes they’ve ever seen.

“The satellite measured trace gases in the atmosphere in order to monitor the ozone and climate. It showed that this year’s ozone hole started earlier than usual, and had a big extension,” said Zehner.

Experts believe the hole in the ozone is not likely to increase warming on the surface of Antarctica.

“It’s not a concern for climate change,” said Zehner.

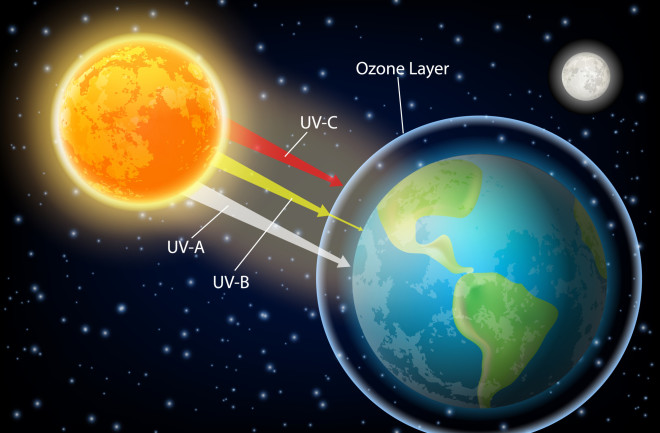

The ozone layer is a trace gas in the stratosphere, one of the four layers of the Earth’s atmosphere.

It functions as a protective gas shield that absorbs ultraviolet radiation, protecting humans and ecosystems from dangerous amounts of UV. Most skin cancers are caused by exposure to high amounts of UV radiation, so anything that shields us from UV rays helps reduce cancer rates.

The size of the ozone hole over Antarctica fluctuates each year, opening each year in August and closing again in November or December.

Zehner said the ozone hole opens up because of the rotation of the Earth causing specials winds over the closed landmass of Antarctica.

“The winds create a mini climate, creating a shield over Antarctica preventing it from mixing with surrounding air. When the winds die down, the hole closes,” he said.

Scientists believe this year’s big ozone hole could be due to the volcanic eruptions at Hunga Tongain Tonga during December 2022 and January 2023.

“Under normal conditions, gas released from a volcanic eruption stays below the level of the stratosphere, but this eruption sent a lot of water vapor into the stratosphere,” said Zehner.

The water had an impact on the ozone layer through chemical reactions and changed its heating rate. The water vapor also contained other elements that can deplete ozone like bromine and iodine.

“There isn’t much evidence the ozone hole is due to humans,” Zehner said.

While this year’s Antarctic ozone hole was likely due to a volcanic eruption, scientists became aware that human activities were creating huge ozone holes in the 1970s.

Ground and satellite-based measurements detected the holes, which were caused by widespread use of chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons.

“The culprit behind ozone depletion was not aerosols in aerosol cans, but the propellants we use as gases to propel the solutions inside. These gaseous propellants contain chlorine, which is released high in the stratosphere and depletes the ozone,” said Jim Haywood, a professor of atmospheric science at University of Exeter in the UK.

The world took action after scientists raised alarm over the ozone holes, and quickly. In 1987,The Montreal Protocol was created to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of these harmful substances.

The good news is that the protocol was effective — ozone holes got smaller in the decades after ozone-depleting gas emissions were controlled.