How recycling urine could help save the world – Report

By Nneka Nwogwugwu

On Gotland, the largest Island in Sweden, fresh water is scarce. At the same time, residents are battling dangerous amounts of pollution from agriculture and sewer systems that causes harmful algal blooms in the surrounding Baltic Sea. These can kill fish and make people ill.

To help solve this set of environmental challenges, the island is pinning its hopes on a single, unlikely substance that connects them, human urine.

Starting in 2021, a team of researchers began collaborating with a local company that rents out portable toilets. The goal is to collect more than 70,000 litres of urine over 3 years from waterless urinals and specialized toilets at several locations during the booming summer tourist season.

The team is from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) in Uppsala, which has spun off a company called Sanitation360.

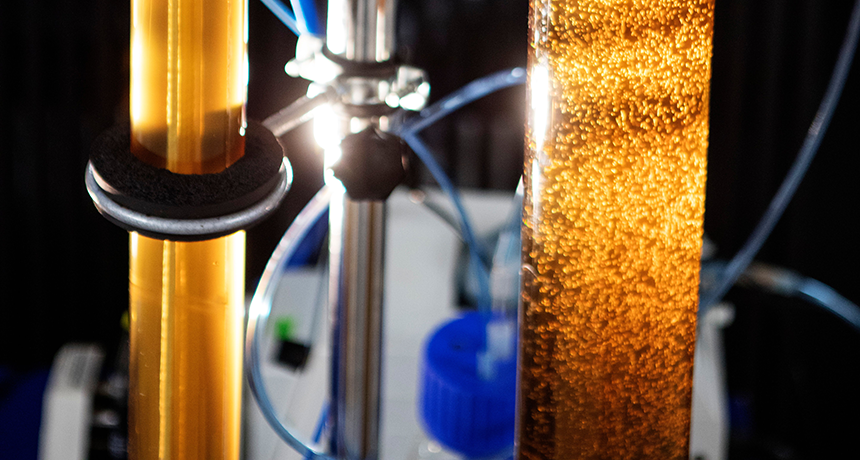

Using a process that the researchers developed, they are drying the urine into concrete-like chunks that they hammer into a powder and press into fertilizer pellets that fit into standard farming equipment.

A local farmer uses the fertilizer to grow barley that will go to a brewery to make ale — which, after consumption, could enter the cycle all over again.

The researchers aim to take urine reuse “beyond concept and into practice” on a large scale, says Prithvi Simha, a chemical-process engineer at the SLU and Sanitation360’s chief technology officer.

The aim is to provide a model that regions around the world could follow. “The ambition is that everyone, everywhere, does this practice.”

The Gotland project is part of a wave of similar efforts worldwide to separate urine from the rest of sewage and to recycle it into products such as fertilizer.

That practice, known as urine diversion, is being studied by groups in the United States, Australia, Switzerland, Ethiopia and South Africa, among other places.

The efforts reach far beyond the confines of university labs. Waterless urinals connect to basement treatment systems in offices in Oregon and the Netherlands.

In Paris, there are plans to install urine-diverting toilets in a 1,000-resident eco-quarter being built in the 14th district of the city.

The European Space Agency is to put 80 urine-diverting toilets into its Paris headquarters, which will begin operating later this year. According to proponents of urine diversion, it could see uses in sites from temporary military outposts to refugee encampments, rich urban centres and sprawling slums.

Scientists say that urine diversion would have huge environmental and public-health benefits if deployed on a large scale around the world. That’s in part because urine is rich in nutrients that, instead of polluting water bodies, could go towards fertilizing crops or feed into industrial processes.

According to Simha’s estimates, humans produce enough urine to replace about one-quarter of current nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers worldwide; it also contains potassium and many micronutrients (see ‘What’s in urine’).

On top of that, not flushing urine down the drain could save vast amounts of water and reduce some of the strain on ageing and overloaded sewer systems.