Climate change threatens Morocco’s camels, cultural heritage survival

By Abbas Nazil

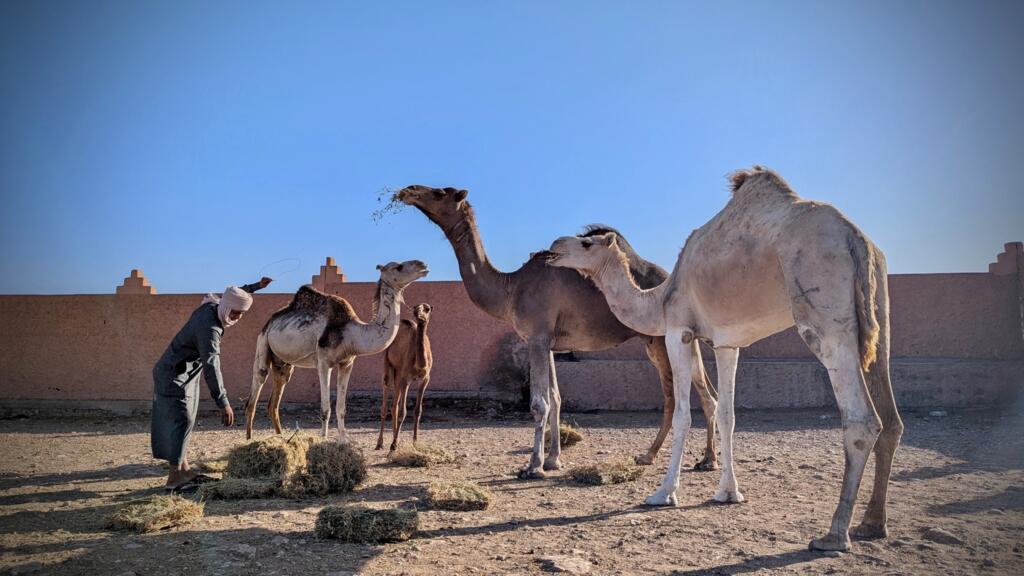

Camel populations in Morocco are facing a significant decline as climate change and shrinking pastures threaten the livelihoods of desert communities.

The Amhayrich camel market, located just outside the southern Saharan town of Guelmim, is the largest in the country and remains a central hub for camel trading throughout the year.

For generations, camel breeding has been an integral part of life in southern Morocco, providing not only meat and income but also employment and cultural significance.

Mohammed, a 33-year-old breeder, explained that camels are considered family members and cultural treasures, with gifting a camel seen as one of the highest honors in the region.

Over the past decade, Morocco has experienced more frequent and severe droughts driven by global warming, significantly reducing the availability of natural grazing vegetation for camels.

Mouloud, a 39-year-old herder, noted that the increasing costs of maintaining camel herds, including the need to purchase fodder, have made breeding increasingly difficult.

The price of camels, particularly stallions, has surged, and herders’ salaries, ranging between €300 and €400 per month, add to the financial strain.

Recruiting skilled herders within Morocco has become challenging, forcing breeders to rely on workers from Mauritania who typically remain for only a short period.

In addition to drought, the traditional grazing areas for camels are shrinking due to agricultural expansion, made possible by the exploitation of underground water resources, further straining camel husbandry.

Camel breeding in Morocco is primarily focused on meat production, which in 2023 amounted to around four thousand tonnes, compared to 257 thousand tonnes of cattle meat in 2022, highlighting the smaller scale of the industry.

While camel breeding faces challenges in Morocco, northern Kenya has seen a rise in camel adoption due to recurrent droughts that have devastated cattle herds, with camels providing a more resilient alternative.

Camels in Kenya can graze on dry vegetation, survive without water for extended periods, and produce significantly more milk than cattle, offering both nutritional and economic benefits.

Since the launch of a camel development program in Samburu County in 2015, camels have helped reduce malnutrition in drought-affected regions and have positioned Kenya as the world’s leading camel milk producer, with annual production reaching approximately 1.165 million litres.

Kenya’s northern and southern pastoral counties house nearly 80 percent of the country’s camel population, totaling around 4.72 million animals, demonstrating the species’ vital role in food security and climate resilience.

The decline of camel livestock in Morocco poses not only economic challenges but also threatens the cultural heritage and traditional way of life of Saharan communities.

Efforts to address these challenges are critical for sustaining the livelihoods, food security, and cultural practices of desert populations as climate change continues to reshape ecosystems across North Africa.